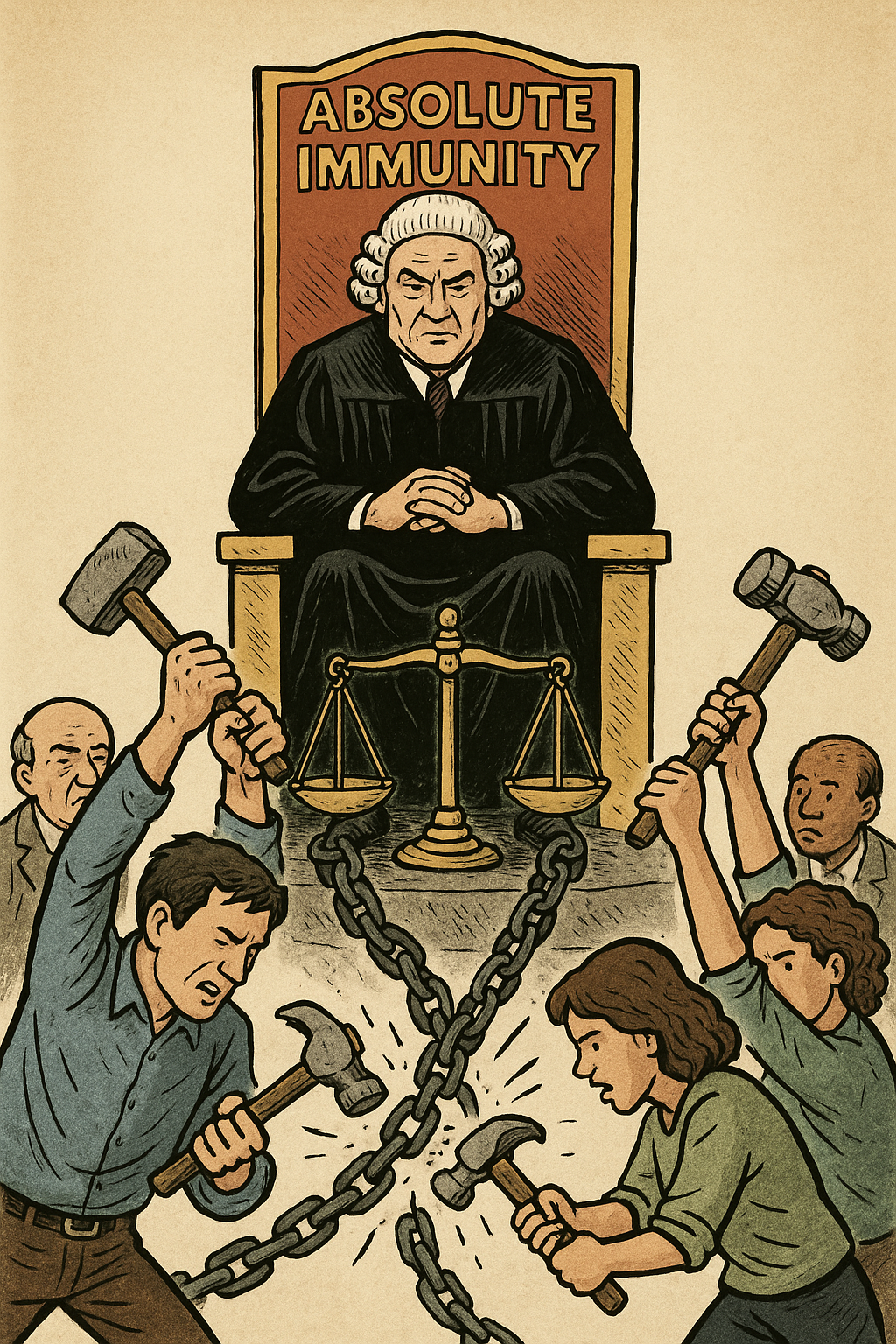

Thesis. Absolute judicial immunity is a judge-made doctrine that overreaches the Constitution’s text and structure, erases the remedial principle at the heart of Marbury v. Madison, and collides with the Fourteenth Amendment’s command that rights be effectively enforceable. Where immunity blocks any consequence for deliberate or reckless violations of law, it converts “a government of laws, and not of men” into the opposite. Ending absolute immunity for bad-faith or clearly unlawful judicial acts—and replacing it with real, bounded liability—restores constitutional accountability without chilling good-faith judging.

I. Text and Structure: Rights Require Remedies

- Marbury’s remedial core. Marbury v. Madison teaches that “where there is a legal right, there is a legal remedy.” Rights without redress are a contradiction in terms; courts cannot simultaneously declare what the law is and declare themselves untouchable when they knowingly violate it.

- Oath and “good Behaviour.” Article VI requires judges to swear to the Constitution; Article III conditions tenure on “good Behaviour.” A regime that forecloses any civil consequence for intentional constitutional violations reads those provisions as empty ceremony.

- Separation of powers properly understood. The Federalist No. 78 defends judicial independence because the judiciary has “judgment” but “neither force nor will.” Independence is not impunity. The Federalist No. 51’s checks-and-balances model presumes no actor is the final judge in his own cause. Absolute immunity eliminates the checking function for the one branch least electorally accountable.

II. Reconstruction Enforcement: The Fourteenth Amendment and § 1983

- Textual authority to create real remedies. Section 5 empowers Congress to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment “by appropriate legislation.” The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 (now 42 U.S.C. § 1983) creates damages actions against state actors who deprive persons of federal rights. It contains no judge-carveout.

- Judge-made overlay. Pierson v. Ray (1967) and Stump v. Sparkman (1978) imported common-law immunity into § 1983; that was a policy choice, not a constitutional command. When that policy blocks redress for intentional or reckless rights-denials, it defeats § 1983’s core purpose.

- Limited retreat already recognized. The Court itself admits absolute immunity is functional and categorical, not textual—and therefore limited by function. Forrester v. White (1988) denies absolute immunity for non-judicial, administrative acts; Pulliam v. Allen (1984) affirmed that injunctive relief against judges may be available (later narrowed by statute). These cracks show the doctrine is not sacrosanct.

III. The Problem in Practice: Stump, Mireles, and Beyond

- Overbreadth in application. In Stump, a judge who approved a secret sterilization petition was absolutely immune because the act was “judicial” and not in clear absence of jurisdiction. In Mireles v. Waco (1991), a judge who allegedly ordered violent seizure of an attorney was still immune. These are not edge-cases; they reveal a doctrine that forgives the unforgivable so long as the form looks “judicial.”

- Referral and impeachment are not remedies. Judicial-conduct commissions are structurally limited and statistically reluctant to discipline for constitutional injuries; impeachment is vanishingly rare. Salary clawbacks or internal reprimands do not restore liberty, property, or due process to the person harmed. None of these mechanisms satisfies Marbury’s remedial principle.

IV. International and Comparative Benchmarks

- Effective remedy is a baseline right. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Art. 8) and the ICCPR (Art. 2(3), which the U.S. has ratified) require “effective” remedies for rights violations. While the ICCPR is not self-executing, it expresses a widely accepted rule-of-law norm: independence of judges coexists with accountability for intentional abuses. Immunities exist in many systems, but they are qualified and proportional, not absolute in the face of bad faith.

V. A Narrow, Workable Replacement: Independence with Accountability

Abolishing absolute immunity does not mean exposing judges to ordinary negligence suits or policy disagreements. It means recognizing civil liability (and related prospective relief) only for egregious, rights-violating conduct under carefully drawn standards:

- Mens rea and scope. Liability attaches only where a plaintiff proves by clear and convincing evidence that the judge acted (a) in bad faith or with reckless disregard of clearly established constitutional rights, or (b) in clear absence of all jurisdiction, or (c) through non-judicial acts (already outside absolute immunity under Forrester). Good-faith legal error remains protected.

- Procedural safeguards.

- Heightened pleading and an early, interlocutory review filter out disgruntled-litigant suits.

- Qualified-immunity-like screening for close calls preserves decisional freedom where the law was not clearly established.

- Specialized venuing (e.g., a neutral panel from outside the judge’s circuit/state) reduces local retaliation fears.

- Remedies calibrated to the wrong.

- Prospective relief (declaratory/injunctive) when ongoing violations are likely, with Ex parte Young-style constraints.

- Damages for proven intentional or reckless constitutional injuries; indemnification by the state presumptively available for good-faith mistakes but recoupment permitted for willful misconduct.

- Discipline that isn’t toothless. Parallel to civil remedies, require publicly reportable disciplinary outcomes and mandatory referral to removal mechanisms when bad-faith constitutional violations are found. Sunshine is part of the remedy.

VI. Answering the Counterarguments

- “This will chill judging.” The standard targets bad faith and reckless disregard, not difficult legal calls. Judges already navigate reversals, recusal motions, mandamus, and reputational scrutiny; calibrated liability for intentional rights-denials will not deter conscientious judging any more than qualified immunity deters conscientious policing.

- “Floodgates!” Heightened pleading, early dismissal, and fee-shifting for frivolous suits close that gate. Experience with qualified-immunity regimes shows courts are fully capable of dispatching weak cases at the threshold.

- “Separation of powers.” Separation of powers forbids domination by any branch—including the judiciary. Congress’s § 5 power exists to enforce constitutional rights against state actors, judges included; carefully framed remedies respect independence while restoring accountability.

- “Appeals are enough.” Appellate review corrects future error; it does not compensate past constitutional injuries—or deter willful lawlessness that can never be reached on appeal because immunity blocks the suit at the starting line.

VII. Bottom Line

Absolute judicial immunity for deliberate or reckless violations is inconsistent with Marbury’s remedial principle, the Fourteenth Amendment’s enforcement mandate, the structure of checks and balances, and basic rule-of-law norms. Real accountability requires the possibility of personal consequence in defined, egregious cases. Anything less—referrals without teeth, discipline without transparency, remedies without damages—preserves the problem immunity created.

No responses yet